Standardized Terminologies Explored

- The Beginnings of Nursing Terminology Development

- Progress of the Use of Documentation

- What Is a Standardized Terminology?

- Why Are There So Many Nursing Terminologies?

- Why Can’t We Document with Natural Language and Free Text?

- Vocabulary Useful in Discussing Standardized Terminologies

- Why Does Nursing Need a Standardized Terminology?

The Beginnings of Nursing Terminology Development

Although today in many countries there is interest in standardized nursing terminologies, the development of nursing terminologies began in the United States (US).1 Clark posits that the reasons probably have do with the US health financing systems and philosophy of nursing education. It was the early 1970s when work began on the first two standardized nursing terminologies. The North American Nursing Diagnoses Association was developed when two nurses discovered that they could not computerize nursing care. At about the same time the Omaha Visiting Nursing Association started development on the Omaha System as a way to simplify nursing documentation while providing the needed information for continuity of care and billing. Since that time, seven nursing specific terminologies have been developed and recognized by the American Nurses Association (ANA), along with two interdisciplinary terminologies that have a nursing component. One of these terminologies, the Patient Care Data Set was retired in 2006.

The writings of Bertha Harmer 2 and Faye Abdellah formed a background for what we now know as nursing diagnosis.3. Bertha Hamer introduced the idea of nursing as a science in her 1921 textbook The Principles and Practice of Nursing.1,2 The science was to be built by identifying and analyzing nursing’s phenomenon of concern. Dr. Faye Abdellah put forth the idea that nurses could identify and solve specific problems, which she organized into a typology of 21 nursing problems. These problems were then classified into three overall categories: 1) physical, sociological, and emotional needs of patients; 2) types of interpersonal relationships between the patient and nurse; and 3) common elements of patient care. 4. Dr. Abdellah also promoted the idea that nursing research was a key factor to help nursing become a true profession.

The promotion by the US Joint Commission since its inception in 1951of the need for adequate patient records and high standards of nursing documentation was another factor leading to the creation of nursing terminologies. Another driving factor was the development in the 1960s of the reimbursement systems that relied on “detailed records of patient diagnoses and professional activities."1 However, to develop today’s terminologies, it took work by many farsighted nurses such as Harriet Werley and Normal Lang and terminology developers such as Virginia Saba and Karen Martin who understood that the omission of nursing data from healthcare records would continue nursing’s invisibility.

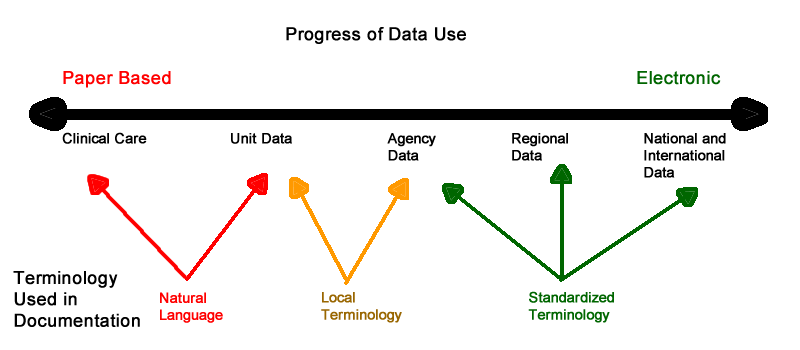

Progress of the Use of Documentation

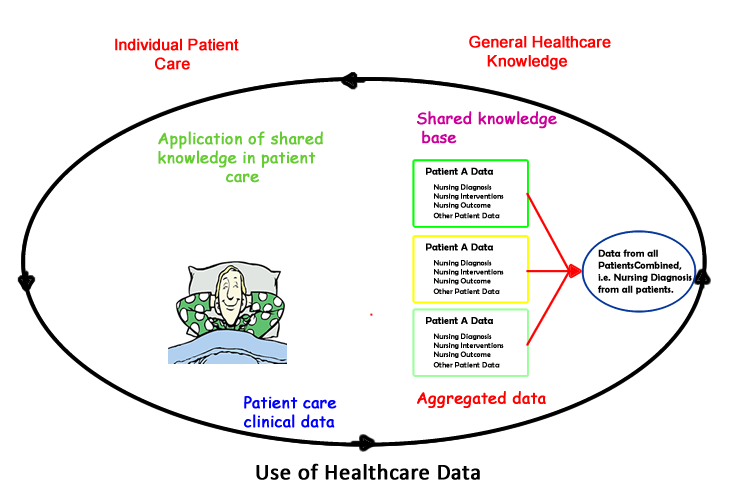

Before the advent of computers, healthcare provider documentation was contained in paper clinical records and focused only on the care of one patient. Because of their nature, using the rich data in a healthcare record to learn more about disease conditions, treatments, and outcomes was prohibitively expensive. If this data was even used it was by researchers, usually with a grant.

Computers have changed this picture. As you can see in the diagram below, healthcare and nursing documentation have progressed from primarily being used to care for one patient to use in analysis at the unit, agency, regional, national, and international levels. Nursing can only be represented beyond the care of one patient, or unit or agency when our documentation uses a standardized terminology.

What Is a Standardized Terminology?

A standardized terminology is one in which the users have agreed that a given term has a specific meaning. A very simple example of a standardized terminology is the terms that you see in a drop-down box, most of which are probably agency developed and used versus part of a nationally recognized standardized language. Standardized terms provide not only a definitive means of communication, but also the ability to analyze data. Currently the U.S. has designated the Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) as the standard for assessment data (including nursing assessments) and the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terminology (SNOMED-CT) as the standard for clinical documentation.

Why Are There So Many Nursing Terminologies?

Nursing terminologies were developed to meet perceived needs. As different organizations developed terminologies, they became stakeholders in the use of these terminologies. This resulted in an unfortunate situation leaving nurses confused over which terminology to use. Attempts at harmonization or matching terms and concepts are difficult. Because the terminologies were often created for different purposes, this discrepancy is not surprising.

The situation today with many different nursing standardized terminologies is reminiscent of the situation faced by American railroads before 1883. On small railroads, the time used was the sun time of the major city, while longer railroads use the sun time several cities 5 because every. This created a situation in which when it was new in Washington DC, it was 12:24 PM in Boston, 12:12 in New York, 12:02 in Baltimore, 11:48 AM in Pittsburgh, 11: 53 in Buffalo, 11: 31 and Cincinnati, and 11: 07 in St. Louis. The state of Wisconsin had 38 different times creating major difficulties for travelers moving from one end of the state to the other. In 1883, after the railroads had had enough of the time confusion on November 18 at new they established a general time convention which divided the United States and four standard time zones.

Fortunately the problem of multiple nursing terminology is being solved by the nursing working group of SNOMED and the ICN.6 A collaborative agreement signed in 2010 to work together to create a clinically useful standardized nursing terminology that can either be used alone or be mapped to from any of the standardized terminologies. This will create a situation in which nursing data can be represented in healthcare data used at the policy making level.Why Can’t We Document with Natural Language and Free Text?

Natural language, or the words that we use in everyday conversation, is the most expressive communication available. However, much of our understanding of natural language depends on context. For example, the terms "below normal," "cold," and "hyper" depend on context and individual interpretations. When used in electronic documentation in the form of free text they are difficult to analyze. Although as computers have grown more powerful the science of Natural Language Processing (NPL) has become more useful in analyzing data, it generally works best, when confined to one, often small, area of content. There is still much room for development before NPL will be useful in all clinical documentation as the many published articles on this topic atest. 6,7,8, 9

Natural language also has many terms, which are often gradations of the same meaning. Unfortunately, the computer does not possess a human’s ability to differentiate these meanings. Additionally, as you may have discovered, computers are black and white instruments. There is no gray area in computer interpretations. To a computer a semicolon (;) and a colon (:) are as different as a mountain and water. Although a human is capable of interpreting the terms myocardial infarction, M I, and heart attack as having similar meanings, to a computer these are three different conditions. Generating all the various terms that are used to mean heart attack would create a situation in which data retrieval and analysis would be unwieldy. Using one term, and only one term, for a given meaning, permits data analysis that can improve patient care.

Vocabulary Useful in Discussing Standardized Terminologies

It sometimes seems as if those who develop or talk about terminologies speak a different language. When you understand this vocabulary, which is not difficult, you will have a better appreciation of the differences and similarities in the various terminologies.

- Granularity

- Linear List

- Taxonomic Classification

- Combinatorial

- Compositional

- Ontology

- Interface or Reference

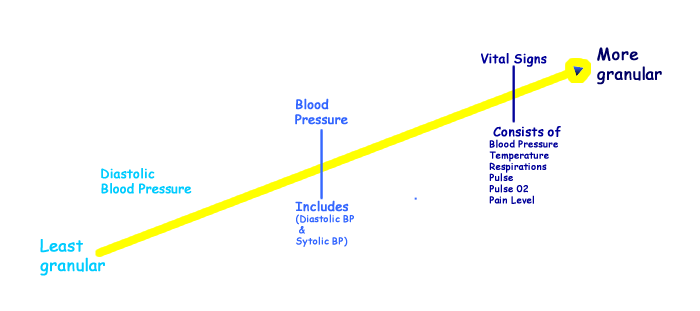

Although most of terminology vocabulary is used to describe an entire terminology, there is one term that is best reserved for individual terms in a terminology: granularity. It refers to the level of data that a term can be used to capture. For example, diastolic blood pressure is a very granular term; it captures a discrete piece of data. This type of data is often referred to as atomic level data. Blood pressure, however, although it is a fairly granular term, is less granular because it consists of more than one piece of data. Vital signs are at an even less granular level. Clinical documentation generally needs terms that are granular, or that capture a precise level of data. Many nursing terminologies have terms at various levels of granularity.

A linear list is a list of terms, which may be organized alphabetically, or by various categories. Drop down lists are an example. The first version of the North American Diagnosis Association International (NANDA-I) was an alphabetical list of the terms. Other names for a linear list are vocabulary or a nomenclature.

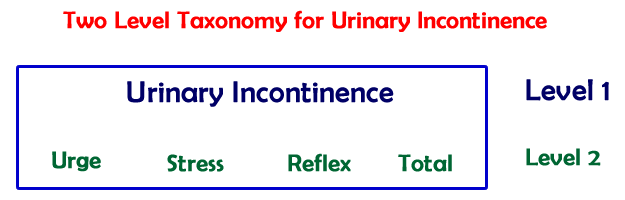

Linear lists are often organized into taxonomies. In the figure below you can see a taxonomic classification for urinary incontinence. A taxonomic classification allows retrieval and analysis at more than one level. For example, in the classification that you see you could retrieve aggregated data for all patients with urinary incontinence or with one or any combination of the conditions at Level 2. To answer questions about outcomes you could add to your query such criteria as interventions, and the presence or absence of pressure ulcers.

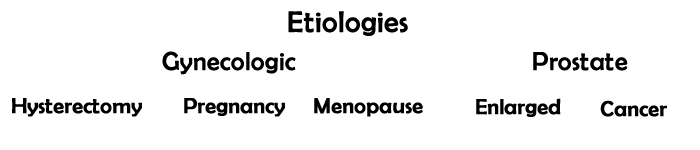

In a combinatorial terminology, the user creates the term for documentation by selecting a term from more than one classification or list. The International Classification of Nursing Practice (ICNP) and LOINC are examples of combinatorial terminologies. In the example above of urinary incontinence classification, a fuller picture could would be gained by adding other standardized terms from, for example a taxonomy of etiologies. This allows the creation of a standardized term of “enlarged prostate stress incontinence.”

A combinatorial terminology provides for more descriptive terms without the need for unmanageable lists, as well as allowing the computer to automatically code these terms as a whole and as individual terms. Combinatorial terminologies often have categories whose terms that are not always needed to describe a condition. For example, a category for location with terms such as left arm, and left leg might not always be needed in a definition. To make documentation easier with combinatorial terminologies, common useful terms, known as pre-coordinated terms are created for use in clinical documentation.

A compositional terminology is a step above a combinational terminology. In a pure combinational terminology, there is the possibility of creating terms that do not make sense, such as total incontinence of the left leg. A compositional terminology avoids this by appling a set of rules that dictate how the terms may be combined.

An ontology is a formal representation of domain knowledge. It consists of a conceptual hierarchy with a shared vocabulary designating the types, properties, and relationships of these concepts. Ontologies are organized by meaning. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ontology_%28information_science%29

Another way of describing terminologies is by how they are used. Clinical terminologies have two purposes, one is for use in documenting patient care, the other for analyzing data. Those terminologies used for documentation are known as interface terminologies. Although analysis can be performed using data from an interface terminology, terminologies designed for analysis are known to as reference terminologies. They contain concepts (a concept is not necessarily a term), in a formal, machine-usable definition that can be understood and communicated without human interpretation. Interface terms are often “coded” behind the scenes by the computer to a reference terminology. With the exception of the International Classification of Nursing Practice (ICNP), and the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED), the standardized nursing terminologies are mostly at the nomenclature level, although there is some classification.

Why Does Nursing Need a Standardized Terminology?

That nursing documentation in a standardized format is valuable was seen as early as 1988. A study was published then that demonstrated that nursing diagnoses were a more accurate predictor of cost of care and length of stay than the diagnosis related groups (DRGs).10 Another study found that when nursing diagnosis are collected from the patient record and combined with a medical diagnosis, variance in commonly studied outcome variables such as length of stay, total charges, and discharge to a nursing home are more easily explained. 11. Medical diagnoses alone do not adequately explain that nursing component of patient care, or provide a complete picture of patient care.

In a 1998 article in the American Journal of Nursing, a situation in which executive officers have little idea of what nurses actually do was discussed. One chief executive stated to his chief financial officer:

“To tell you the truth George I do not know what RNs do. Every time I have been on walking rounds in this hospital and asked nurses what they have done recently for our hospital’s survival, some tell me I should already know, others struggle to come up with an answer, but cannot explain. I know we need some RNs here but I am not sure why.” 12 p42

How would you answer this CEO? Would you be able to tell him that we not only carry out physician orders, but assess our patients, identify problems that we are licensed to treat, plan and implement interventions, and evaluate the outcomes? Would you have the language to document this in a way that it could be analyzed? Despite being one of the most significant contributors to patient care, our contributions and observations are rarely included when data is abstracted from healthcare records. It is only through the use of standardized terms, that nursing’s data will be added to the data that is analyzed in healthcare. Lacking a way to analyze our care also prevents evidence-based care and perpetuates care based on “what we have always done.”

It is not uncommon for nursing care to be assessed using “outcomes potentially sensitive to nursing.” These outcomes include such things as the incidence of urinary tract infections, pressure ulcers, pneumonia, shock, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Although the presence or absence of these conditions can indicate the quality of nursing care, there may be other contributing factors that are not considered. For example, a recent article demonstrated that pressure ulcers are not always a result of poor nursing care, but that physician preferences for sustained positions in the operating room can be a major contributing factor.13 However, when our interventions and outcomes are not documented in a way that allows them to be analyzed together with other factors, pressure ulcers and other conditions with more than one contributing factor will continue to be seen as a failure of nursing.

Additionally, much of nursing is cognitive and we are knowledge workers. However, when this aspect of nursing is not recognizable in healthcare records it is not acknowledged. The result is that some administrators believe that nurses can be replaced with personnel who have minimal training, minimal knowledge, and only require minimal pay. To remedy this we need to have documentation that demonstrates these processes as well as uses terms that can be included in aggregate analysis at higher levels and in creating healthcare policy.

References

1. Clark J. The International Classification For Nursing Practice Project. Online Journal Nursing Informatics. 1998;3(2). http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANA

Marketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Vol31998/

No2Sept1998/TheInternationalClassificationForNursing

PracticeProject.html.

2. Boschma G, Davidson L, Bonifacio N. Bertha Harmer's 1922 textbook - The Principles and Practice of Nursing: Clinical Nursing from an Historical Perspective. J. Clin. Nurs. Oct 2009;18(19):2684-2691.

3. Orunmuyiwa G. Faye Abdellah's 21 Nursing Problems. http://21typologyofnursingproblem.blogspot.com/ . Accessed June 8, 2014.

4. 21 Nursing Problems by Faye Abdellah. 2013; http://nursing-theory.org/theories-and-models/Abdellah-twenty-one-nursing-problems.php . Accessed June 8, 2014.

5. Kisor H. Zephyr: Tracking a dream across America. New York: Times Book; 1994.

6. Ferraro JP, Daumé H, DuVall SL, Chapman WW, Harkema H, Haug PJ. Improving performance of natural language processing part-of-speech tagging on clinical narratives through domain adaptation. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. September 1, 2013 2013;20(5):931-939.

7. Kang N, Singh B, Afzal Z, van Mulligen EM, Kors JA. Using rule-based natural language processing to improve disease normalization in biomedical text. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. September 1, 2013 2013;20(5):876-881.

8. Nadkarni PM, Ohno-Machado L, Chapman WW. Natural language processing: an introduction. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. September 1, 2011 2011;18(5):544-551.

9. Heintzelman NH, Taylor RJ, Simonsen L, et al. Longitudinal analysis of pain in patients with metastatic prostate cancer using natural language processing of medical record text. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. September 1, 2013 2013;20(5):898-905.

10. Halloran EJ, Kiley M, M. E. Nursing diagnosis, DRGs, and length of stay. Appl. Nurs. Res. 1988;1(1):22-26.

11. Welton J, Halloran E. Nursing Diagnoses, Diagnosis-Related Group, and Hospital Outcomes. Journal of Nursing Administration. December 2005;35(12):541-549.

12. Hansten R, Washburn MJ. Professional practice: Facts & impact. American Journal of Nursing. 1998;98(3):42-45.

13. Paul R, McCutcheon SP, Tregarthen JP, Denend LT, Zenios SA. CE: Sustaining Pressure Ulcer Best Practices in a High-Volume Cardiac Care Environment. AJN The American Journal of Nursing. 2014;114(8):34-44 10.1097/1001.NAJ.0000453041.0000416371.0000453016.

Created September 10, 2014